Our justice system has a racial bias problem, both in the way it treats suspects, and the way it treats victims.

The cases of Troy Davis and Trayvon Martin underscore this. If the races were reversed would Troy Davis’ execution have been pursued so relentlessly, would he even have received a death sentence, would police have been so quick to ignore other potential suspects?

And, had the races been reversed, wouldn’t the reaction to Trayvon Martin’s killing have been … different?

But knowing there is racial bias and doing something about it are two different things. In North Carolina, something is being done.

First, some background. On April 22 twenty-five years ago, in a capital case out of Georgia called McClesky v. Kemp, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that there were indeed racial disparities in who gets sentenced to death. A study of Georgia’s death sentencing patterns, known as the Baldus study, did indicate “a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race” the Court held.

But, bizarrely, the High Court ruled that this evidence of systemic racial bias didn’t matter. Unless discrimination could be proven in a specific case (McClesky’s), they would do nothing. System-wide bias was irrelevant.

The Court was concerned that if systemic biases were taken into account in death penalty cases, the contagion would naturally spread to other cases. Justice Lewis Powell wrote fatalistically

“Apparent disparities in sentencing are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.”

He worried that “we could soon be faced with similar claims as to other types of penalty.” If this wasn’t nipped in the bud, judges might have to do something about racial bias in ALL cases!

The 4 dissenters in the case wrote that this “seems to suggest a fear of too much justice.”

In 1987, Justices of our highest court prevented this outbreak of “too much justice” by turning their robed backs on claims of systemic racial bias. Justice Powell later regretted this decision, but the damage was done. Today, racial bias continues to permeate every stage of our criminal justice system, a system that has exploded to now house one quarter of the world’s prisoners. There also continue to be racial disparities in terms of how victims are treated, and killings like that of Trayvon Martin where there seems to be a complete disconnect in the community along racial lines.

But in 2009 North Carolina tried to overcome the “fear of too much justice” by passing the Racial Justice Act, a law which allows courts to consider statistical evidence of racial bias when deciding whether death sentences are appropriate.

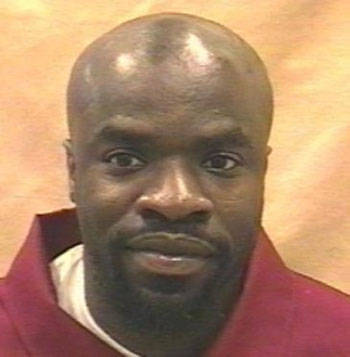

Today, that law was upheld, and Marcus Robinson was resentenced to life without parole due to the significant role race played in North Carolina capital cases at the time of his trial. This decision, the first involving the new Racial Justice Act, is a major step in the right direction.

Twenty-five years ago, the Supreme Court had the chance to address fundamental questions about racial bias in our courts. They punted. Hopefully what is happening in North Carolina means that, 25 years later, we are finally ready to confront race and criminal justice in America.